Medico-legal issues of Shoulder Surgery

Any surgical act always implies a minimal risk of failure. Therefore it is essential to focus on the diagnostic-therapeutic risk factors involved in any given pathology, thus allowing a clear distinction to be made between normal routine situations and challenging conditions.

The increase in surgical medical negligent litigations has probably occurred for various reasons:

- Patient demands and expectations have increased. The patient does not complacently accept a mediocre outcome; putting his/her trust in the "miracle results" claimed by others in similar cases, he expects total healing. The failure to achieve a positive result is often attributed to medical error or institutional deficits, and favourable results cited in similar cases are used as penalising evidence.

- The development of super specialities has brought with it much technological progress, not always obtainable by the individual specialist, who requires a more or less acute learning curve to personally master such progress; it therefore follows that the use of the current practices governed by traditional techniques, although valid, are often considered obsolete by the patient.

- Long-term damaging complications, although rare, are not always clearly and explicitly indicated in the informed consent documentation; such complications are therefore completely unexpected by the patient and automatically attributed to medical negligence.

- A poor doctor-patient relationship based on hurried and incomplete dialogue.

- Presentation of a damages claim, often as a result of superficial medical report or biased interest by a medical or legal representative. Hence it follows that therapeutic failure is concluded by legal representation due to an "assumption of guilt".

There are many areas of medical care that are vulnerable to the risk of failure. Not all of these are under the direct control of the senior surgeon (something which most patients are not aware of). The most important aspects to take into consideration are:

- Correct diagnosis: correct treatment can only follow a correct diagnosis.

- Severity of the disease: the more serious the anatomophysio-pathological alterations are, the more challenging treatment is, and in all likelihood, the less predictable the results.

- Frequency in practicing treatment: The more experience a surgeon has in performing a procedure, the easier it becomes and the better the outcomes. The surgeon improves his/her technique, allowing him to successfully confront delicate and awkward phases of treatment, therefore reducing the risk involved.

- Difficult surgical techniques: despite the experience and ability of the surgeon, the occurrence of errors and complications is directly proportionate to the complexity of the procedure itself.

- Rehabilitation: this is a crucial part of functional recovery and should be considered part and parcel of treatment. The type of rehabilitation practised should be suited to the disease, the surgery performed and the individual needs of the patient.

- Complications (frequency and importance): this particular factor is of substantial significance in the assessment of potential failure of any given treatment. It is a requirement for surgeons to make patients aware of common and significant complications of a particular treatment and weigh this against the risks and benefits of alternative treatments.

- Evaluation of results: There are many published studies on the results of specific treatments. However, these may vary depending on population variances, surgeon's experience and expertise and facilities. Therefore, every clinician should be diligent in knowing his/her own results and auditing them regularly.

The shoulder is unique in that it is a complex of five joints and over thirty muscles. It is the most mobile joint of the body and we are reliant on it to position our hand in space to perform almost all of our daily activities. Thus, any loss of shoulder function or pain is extremely disabling.

The major nerves and blood vessels, which supply the arm and hand pass very close to the shoulder joint and are always at risk of injury. The shoulder joint itself is deep under multiple layers of thick muscles and therefore more difficult to access than most other joints. However, due diligent and careful technique should avoid risk to surrounding structures.

ARTHROSCOPIC SURGERY

Arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery has made access to the shoulder simpler and safer. It has also reduced the risk of complications such as bleeding and infection. For example, the deep infection risk for rotator cuff repair surgery is reduced from 1.9% to under 0.5%. However, arthroscopic surgery requires a different type of surgical skill and expertise to open surgery. It is also costly and requires numerous machines of modern technology to all be working perfectly at the same time. Therefore, the results of arthroscopic procedures are dependent on the following:

- The surgeon's training, experience and abilities: This is similar to an airline pilot, although the training far less stringent or consistent. Nowadays, a specialist shoulder surgeon performing complex reparative arthroscopic procedure should have had at least one year of a specialist shoulder fellowship, in addition to his/her standard orthopaedic training. He should have attended courses on the techniques and shown an aptitude for the skills required.

- Equipment: Arthroscopic shoulder surgery should not be performed without a fluid management pump, shaver unit, radiofrequency unit and good quality visual imaging system. Unfortunately surgeons sometimes do tolerate lesser quality equipment under socio-economic, managerial and patient pressures. This will lead to a higher risk of complications and intra-operative errors.

- Implants: There is sufficient data on the suture-anchors that we use in shoulder surgery to show that the older implants are less strong or resilient as modern implants. Implant failure is thus less likely to occur with modern implants. However, anchors may still dislodge from poor quality bone or tendon tissue.

- Documentation: Arthroscopic surgery is viewed via a camera system, thus image and video recording of the surgery is much simpler than open surgery. A surgeon should keep a visual record of the procedure, ideally in a digital format.

- Post-operative Care: Although the surgery is performed through small incisions the recovery can still take months and post-operative pain needs managing. Good, appropriate and early rehabilitation improves and accelerates the overall recovery.

COMMON SHOULDER PROCEDURES

There are risks common to most shoulder surgical procedures. These include:

- Infection: The deep infection risk with arthroscopic surgery is less than 0.5%, but with open surgery is greater than 1.5%.

- Stiffness: temporary stiffness of the shoulder is common after shoulder surgery, with an overall risk of 5%. This is higher with more complex open surgery and long periods of immobilisation after surgery.

- Nerve injury: Nerve injuries are rare, but can be devastating if permanent. The nerves most at risk are the Axillary nerve (which supplies deltoid and lifts the arm up) and the musculocutaneous nerve (which supplies biceps and bends the elbow). Type of injury include:

- Traction injuries: The nerves around the shoulder can be stretched if too much traction is used during the surgery, or if retracted heavily to allow exposure in open surgery.

- Anaesthetic injury: An interscalene nerve block is often used for pain relief during and after surgery. This involves injecting local anaesthetic in the sheath surrounding the nerves supplying the shoulder and arm. The injection is done in the neck. Rarely, the anaesthetic effect can be prolonged and sometimes lead to long-term nerve pain in the arm. The risk of this is approximately 0.4%.

- Direct injury: Direct injury to nerves around the shoulder should be avoidable by careful surgical technique. However, complex and revision open surgery of the shoulder leads to deformed anatomy, scarred tissues and a higher risk of inadvertent nerve injury, despite due care.

ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR

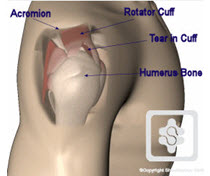

The rotator cuff is essential for normal shoulder movement. If it is traumatically torn in a younger, active patient (generally under the age of 70 years) a repair is required. Likewise, degenerative 'tearing' of the rotator cuff occurs as part of the normal ageing process and can occur more rapidly in some people due to genetic factors. These people do not have a sudden onset of pain and weakness and tend to be older than the traumatic group. They can be managed with non-operative measures of pain control, physiotherapy and sometimes arthroscopic debridement procedures. These rotator cuffs are likely to fail an attempted repair due to the poor muscle and tendon quality.

Sometimes there is an overlap between the two groups, such as when a degenerate tear suddenly ruptures further as a result of a fall and the person then developes pain and weakness. It can be difficult for a surgeon to know before surgery whether the muscle quality will be sufficiently robust to survive a repair. Therefore, the failure rate of rotator cuff repairs is between 12 and 25% in most studies. Despite the failure of the repair, there still is a 95% improvement in pain relief.

The results of open and arthroscopic repairs are the same. The risk of infection is significantly higher with open rotator cuff repairs, but not all surgeons have the skills and facilities yet to perform arthroscopic repairs yet.

Post-operative stiffness is a common complication. It often resolves spontaneously, but can take 12-18 months to fully recover. This can be reduced with good surgical technique (soft tissue releases and a solid repair that allows early and safe mobilisation).

SHOULDER INSTABILITY

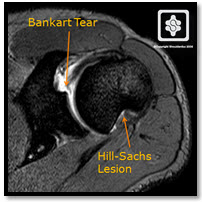

Most shoulder dislocations are 'traumatic'. For example, a rugby player dislocating his shoulder in a tackle. A typical pattern of injuries occur in the shoulder (Bankart lesion and Hill-Sachs lesion). In a younger active person (under 21 years of age) this is usually requires surgical repair, as the redislocation rate is over 80%. In older people it can be managed non-operatively until further dislocations occur, as the recurrence rate is much lower.

'Atraumatic' shoulder instability is a much more complex range of shoulder instabilities to manage. This requires management by a specialist shoulder team (surgeon and therapist) with an interest and expertise in this range of conditions. The role of surgery and rehabilitation is more complex and inappropriate stabilisation surgery can complicate further management and increase morbidity.

The recurrence rate after shoulder stabilisation surgery should be approximately 5%. This does depend on recognition of the pathologies and the correct surgery to address them. I call this 'a la carte surgery'. The results of arthroscopic repair are similar to open repairs, using modern techniques. The surgeon should also have a robust rehabilitation protocol, which is clear and correctly applied by the therapist.

The complication of slight stiffness, particularly with regard to external rotation, until recent years was not evaluated negatively as it lent a certain degree of articular stability. In fact, such types of surgery (Putti-Platt, Magnuson-Stack) set out to correct instability by limiting external rotation. Nowadays, a limitation in external rotation greater than 15° is not well tolerated as most of these patients require full external rotation as part of their working and sports activities.

Any errors in inadequate recognition of the type of shoulder instability, pathological lesions, patient selection and surgical technique are likely to lead to a poor outcome, complications and higher risk of recurrence. Errors in rehabilitation therapy can compromise the final result and increase the risk of failure.

SHOULDER REPLACEMENT

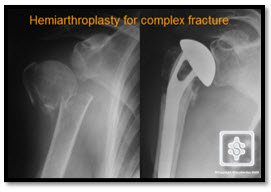

Shoulder replacement is usually performed either for arthritis or complex fractures. The results and risks for the two indications differ substantially. Shoulder replacement for fracture is a 'salvage procedure' to try restore some function and pain relief to a fracture that cannot be fixed. Shoulder replacement for arthritis is similar to replacements of other joints and a common treatment for end-stage arthritis.

Shoulder replacement for fracture is usually a hemiarthroplasty prosthesis (where the fractured humeral component only is replaced). The other bone fragments which hold the rotator cuff are repaired around the prosthesis. The patients are generally old, frail and have osteoporotic, soft bone. Stiffness is common and the success rate (pain and function satisfaction) is no more than 75%. There are many technical difficulties with this surgery and it is uncommon and complex. Serious complications should be minimal, as long as careful surgical technique is applied and the surgery performed by a suitably qualified and experienced surgeon. This should be a specialist upper limb consultant surgeon or senior upper limb Fellow. It is has been well demonstrated in numerous studies that the results of and complication rates of shoulder replacement surgery correlate with surgeon expertise and experience.

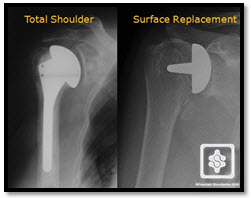

The results of shoulder replacement for arthritis are above 90% improvement in pain relief and over 75% improvement in function. Total shoulder replacements (both sides of the joint are replaced - humeral and glenoid) tend to be slightly better than hemiarthroplasties, but the complications and surgical risks are increased by the increased surgery required to implant a glenoid component as well as a humeral component. Also, the glenoid components are made of polyethelyne, which is inevitably prone to wear away over time and contribute to loosening of the prostheses. There is simply 'more to go wrong'. However, more revision hemiarthroplasties to total shoulder replacements have been performed in large published studies for unsatisfying results such as the persistence of pain, reduction of movement and loss of strength.

The issues of hemiarthroplasty or total replacement have also been confounded by the rapid expansion of the surface replacement prosthesis. This involves simply replacing the surface of the humerus articulation with a prosthesis. The surface replacement procedure is simpler and less invasive than the standard stemmed prostheses, however it is mainly performed as a hemiarthroplsty only. Nonetheless, comparative studies have shown similar results to total shoulder replacements.

A study in the USA [Hasan et al. 2003] showed that seventy five percent of shoulder replacements for arthritis are performed by an orthopaedic surgeon who does only one or two of these procedures per year. The authors suggest that patients may be better off seeing a shoulder specialist surgeon who sees a large volume of cases, siting that the number of times a surgical procedure is performed may have a bearing on how well it is done. This situation is almost certainly the same in the UK. The British Shoulder and Elbow Society have established a shoulder register in order for shoulder surgeons to collectively audit the results of shoulder replacements in the UK. Unfortunately, only the high volume pro-active surgeons contribute to it. Likewise, the published results in the literature are generally only reflective of experienced surgeons in larger centres.

We shall briefly examine some of the individual risk situations:

- Loosening of the glenoid prosthesis: this constitutes the most common cause of failure. Evidence of periprosthetic radiolucency is reported in the various case studies with an incidence ranging between 29 and 83% even though it rarely entails a complete loosening of the implant. Needless to say, the final result is compromised. This appears to be declining with newer glenoid prosthetic designs.

- Post-operative instability: this has an incidence ranging from 0 to 29%. It can manifest itself as a dislocation (commonly superior-anterior) as well as a complete dislocation that can be acute or recurrent. The determining causes are several: subsidence or rupture (pre-existing or secondary) of the rotator cuff, in particular of the supraspinatus or subscapularis, detachment of the prosthetic components (stem or glenoid); faulty positioning of the former in the frontal or sagittal plane; malfunction of the deltoid muscle, etc.

- Intra-operative periprosthetic fractures: these represent a risk factor that should not be underestimated. Their aetiology is characterised as a result of manoeuvres for obtaining good exposure during operation, during preparation of the medullary canal with excessively zealous reaming, or during implantation of an oversized stem. This is more common in soft osteoporotic elderly bone. It is very rare with surface replacement implants.

- Infection is a relatively rare risk factor, statistically constituting approximately 1% of cases. It should be noted that infection usually arises from general and local predisposing factors such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic treatment with corticosteroids or chemotherapy or the co-existence of a septic site in other areas. The manifestation of a septic process can occur during the acute phase (2-3 months from surgery) or later on (1 year or more).

- Nerve lesions also constitute a relatively rare complication. They are usually temporary lesions, with a favourable prognosis. Most commonly affected is the axillary nerve, the musculocutaneous nerve and, more generally, the brachial plexus as a result of retraction and traction manoeuvres during difficult surgery. Periodic nerve tests (EMG) are essential in assessing the evolution of the lesion.

It is quite clear that shoulder replacement surgery is exposed to numerous risk factors whose specific implications for results should be recognised and evaluated prior to treatment. There is no doubt, however, that the incidence of potential failure depends on recognition of difficult and challenging cases beforehand and the surgery being performed by a surgeon of appropriate skill and experience.

SUMMARY

Complications and errors represent a not uncommon event during the course of a therapeutic procedure and open the way to failure causing serious repercussions both on the health of the patient and on the professional status of the physician. Very often, such an event culminates in a medical malpractice suit. For this reason, the study of risk factors is more important than ever, the principle objectives being to:

- emphasise to the patient the difficulties involved in the procedure, the risks and benefits. Sufficient information should be provided in both verbal and written form to allow informed consent.

- remind the physician of the more delicate steps involved in the procedure that require greater caution and a high level of skill and preparation make the doctor aware of the procedures that present particularly difficult problems

- familiarise the legal profession with the implications, risks, and expected outcomes, as well as the gravity of an eventual medical error.

In this review I have highlighted how numerous and important the risk factors predispose to failure are during diagnosis, treatment and recovery of the common and significant shoulder disease and surgical situations.