Glenohumeral Arthrodesis

Although the indications for arthrodesis are diminishing, it still remains an extremely valuable and important method of shoulder management when indicated. It has stood the test of time and can be a reliable method of restoring a limited range of pain-free function to the shoulder. Its primary indication formerly was pain, but with the development of total shoulder replacement, it is rarely done now for primary degenerative reasons. Controversy still surrounds the optimal position for fusion. Because it tends to be used when all else has failed, each procedure must be individualized to take account of the preceding surgery, scarring, infection, loss of bone stock, and specific requirements of the patient.

Indications

Paralysis

Flail shoulder from whatever cause is an indication for arthrodesis. In the Western world until recent decades, anterior poliomyelitis was the most common cause of a flail shoulder. However, as the problems of polio have decreased, the problems of the motor cycle have increased, and severe proximal root and upper trunk brachial plexus injuries are a common indication for shoulder arthrodesis. These patients may have good function in the elbow and hand but are unable to use it because of an inability to place the hand in space. If there is good scapular control (i.e., trapezius, levator scapulae, and serratus anterior functioning), then shoulder arthrodesis allows adequate stabilization for effective hand function. Apart from loss of function, the flail shoulder may develop inferior subluxation, that is purely due to the weight of the arm. This causes severe aching such that the patient may be comfortable only in a sling. This aching is relieved by shoulder fusion.

Post-tumor Resection

Resection of soft tissue tumors around the shoulder may require removal of the deltoid and rotator cuff, which makes reconstruction with arthroplasty difficult because of instability. When soft tissue and bone are removed, specialized techniques may be required, including bone grafting, vascularized bone grafts, and massive allografts.1

Failed Shoulder Replacement

Because of the intense scarring and fibrosis induced by a possible loosened or infected shoulder replacement, removal of the prosthesis alone may give surprisingly good function.2 However, if this fibrous pseudoarthrosis is not adequate for pain relief, then arthrodesis may be a reasonable alternative, although the surgical difficulties in obtaining arthrodesis in this situation can be great.

Instability

Unfortunately, a very small percentage of patients who undergo soft tissue stabilization for recurrent dislocation of the shoulder fail to gain permanent stability through repeated procedures. It is sometimes, although thankfully only rarely, necessary to guarantee bony stability by arthrodesis. In some of these patients, the personality as well as the shoulder may be unstable, and careful preoperative assessment is required. One patient who had a successful arthrodesis for multiple recurrent posterior dislocation was still convinced his shoulder was dislocating even when shown radiographic proof of bony fusion!

Fracture Malunion

Ideally, most of these patients should be treated by some reconstructive procedure or glenohumeral arthroplasty. Sometimes, however, the bony geometry is so grossly destroyed that arthrodesis is the only sensible alternative.

Isolated but total loss of axillary nerve function appears to cause variable disability. In the presence of an intact and functioning rotator cuff, this disability may be minimal. If functional disability is a major problem, however, the choice will be between glenohumeral fusion and multiple muscle transfers. These muscle transfers are probably better reserved for partial axillary nerve palsy; glenohumeral arthrodesis can provide a more reliable method of restoring function if their symptoms justify it.

Flail Shoulder and Elbow

Elbow flexorplasry alone in the presence of a flail shoulder can be disappointing because attempted elbow flexion can result in shoulder extension rather than flexion of the elbow. Shoulder fusion in combination with flexor plasty provides a more useful arm.

Infection

In the past, arthritis that was due to tuberculous infection was the most common indication for shoulder arthrodesis. Although this is still a problem worldwide, in the Western world, it has fortunately become rare. Pyogenic arthritis still occurs and can destroy the shoulder joint. However, the most common cause of infection these days is unfortunately iatrogenic, secondary to previous surgery, for example, infection of internal fixation devices for fractures around the shoulder. A recent history of infection is an absolute contraindication to arthroplasty but may be considered when the infective episode may have happened years before without flare-ups since the original event. Therefore, arthrodesis can provide the most satisfactory alternative.

Contraindications

Patients who are unable to cooperate with an extensive course of rehabuitation after surgery are contraindicated for glenohumeral arthrodesis. Other contraindications are the inability to wear a shoulder spica for some reason, such as skin problems and progressive neurologic disorders. Shoulder arthrodesis relies on the trapezius, levator scapulae and serratus anterior to provide function for the shoulder following fusion. If these are significantly weakened, function will be grossly diminished as the disease progresses.

Preoperative Preparation

It is advisable to make the shoulder spica before operation because this has several distinct advantages. (1) The shell can be bivalved so that it can be easily applied while still under anesthetic at the time of operation. (2) The shoulder spica does not come as too much of a shock for patients, and they can wear it for some time preoperatively to get used to the feeling of being in it. Despite this careful prethinking, this preoperative cast rarely is the definitive shoulder spica throughout the months that patients are in a cast, and a change of cast or adjustment of position is required at 1 to 2 weeks.

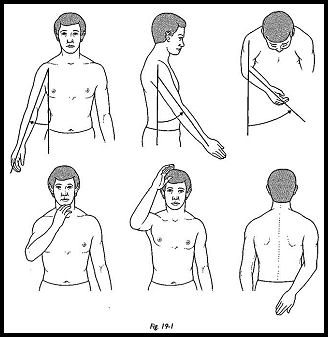

Position of Patient

Many different optimum positions have been described in the literature, and the debate still continues. In 1942 the Research Committee of the American Orthopaedic Committee recommended the salute position, but this was thought to cause an unnecessary degree of abduction and forward flexion; thus, when the arm is lowered to the side of the body, there is a fixed winging of the scapula, causing an uncomfortable strain on the scapulothoracic muscles. Rowe and Zarins3 at the Fourth International Conference on Surgery of the Shoulder 1989 advocated a further modification, which has been widely accepted (Fig. 19-1).

Rowe and Zarins3 recommend that the shoulder should be arthrodesed with enough abduction to clear the axilla; enough internal rotation to reach the midline of the body, both anteriorly and posteriorly; and enough forward flexion to reach the face and head.

After excessive abduction is eliminated, patients can reach their side and back pockets, gluteal area, and feet, and with forward glide of the scapula on the chest wall, they can elevate the arm well above the head. The following points are emphasized:

- Elevation of the arm is not attained by abducting the arm against a fixed scapula, but rather in forward flexion using the normal forward glide of the scapula along the chest wall.

- When abduction of the arm is eliminated, the lifting fulcrum is central to the body, with the scapula in neutral position. Lifting is found to be stronger and more comfortable because the leverage of the arm is not functioning against a rotated or winged scapula.

- Cosmetically, the scapula with the arm at the side of the body is flat on the chest wall and not 'winged. The patient does not have the sensation that his arm is in the way.

- The sleeping position is much more comfortable. Most important is that the patient can sleep peacefully on the side of the arthrodesed shoulder.

The patient is placed in the sitting position, and the arm is draped separately.

Technique

The incision extends from the spine of the scapula to the anterior acromion and down the anterior aspect of the shaft of the humerus.

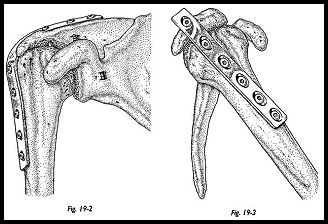

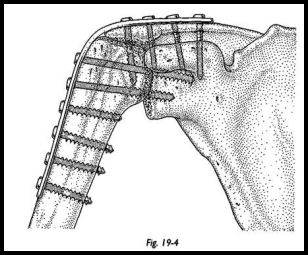

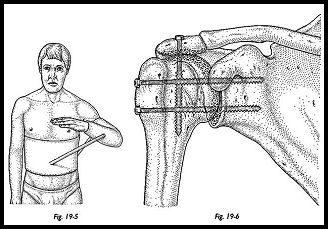

The deltoid is detached from the anterior acromion, and its fibers are split distally. The rotator cuff is resected. The undersurfaces of the acromion, the glenoid fossa, and the humeral head are decorticated. Because the glenoid fossa offers such a small area for fusion with the humeral head, an attempt is made to obtain arthrodesis between the acromion and the humeral head by upward subluxation of the humeral head. It is important not to fracture the acromion downward to meet the humeral head, because this causes significant disturbance of the shoulder "skyline"; it can be cosmetically unacceptable in women and cause difficulty with clothing because straps and shoulder pads slip down. A 10-hole 4.5-mm pelvic reconstruction plate is used. The humeral head is brought proximally to appose the decorticated undersurface of the acromion (Figs. 19-2 and 19-3). When the humerus is abducted and flexed, the position is maintained by supporting the arm with sterile folded sheets, and an assistant is asked to maintain this position during the rest of the procedure. The optimum position is assessed clinically, because this has been shown to be accurate to within 10 degrees.4

Intraoperative radiographs are not routinely used. The plate is contoured using hand-held bending irons. The plate runs along the spine of the scapula over the acromion and down on to the shaft of the humerus. The three screws passing through the plate and into the humeral head into the glenoid fossa are inserted first. These screws compress the arthrodesis site. The cortical screw should be directed next from the spine of the scapula into the base of the coracoid process. A further cancellous screw is placed across the acromiohumeral fusion site, and the remaining holes of the plate are secured with screws. The bivalved plastic shoulder spica is applied under anesthesia on the operating table. A fixed abduction shoulder brace may be used (Figs. 19-4 to 19-6).

Postoperative Management

Comfort dictates the change of cast, but this is usually at about 2 weeks. At 8 weeks postoperatively if there is no radiographic sign of loosening of the internal fixation, the cast is removed and the patient placed in a sling. A gentle range of motion exercises are allowed until radiographic evidence of union is finally achieved. It is difficult to be certain exactly when fusion truly occurs, because the rigid fixation creates very-little callus, but 4 months is an average time to fusion.

Because no two shoulder arthrodeses are alike, the adequacy of fixation must be assessed at the time of operation. If there is any doubt that bony fusion will occur easily, then iliac crest corticocancellous graft is added.

Complications

Nonunion

Published rates of nonunion are as variable as the indications for surgery. It is rare to see a nonunion when the indication for fusion has been a brachial plexus lesion. Usually in this situation the bony geometry is maintained. There may have been little previous bony surgery and little scarring within the joint itself. However, in the presence of infection and bone loss, the nonunion rates increase accordingly. In Cofield and Briggs5 in a series of 71 arthrodeses, only 3 resulted in nonunion. These three were successfully fused following a second operative procedure.

Malposition

Hyperabduction is the most common malposition at surgery. Adult patients have great difficulty adapting to positions of more than 45 degrees of abduction. If too much internal rotation has been incorporated, then the patient cannot easily bring his hand to mouth or reach front or back pocket, and a correctional rotational osteotomy may be required.

Prominence of Internal Fixation Device

Because of gross muscle wasting and atrophy around the shoulder in many of the patients requiring arthrodesis, the internal fixation plate may come to He in a very subcutaneous position in thin patients. It may be troublesome, requiring removal.

Fracture of the Humerus

The AO Group recommends prophylactic bone grafting because of the incidence of fracture at the distal end of the internal fixation device. Cofield and Briggs5 also confirmed this, in that 10 of their 71 patients also presented with a fracture in the fused extremity. It is not known whether prophylactic removal of the internal fixation plate can reduce this incidence of fracture.

Insufficient Range of Motion

It has been advocated that the range of motion following a glenohumeral arthrodesis can be improved and discomfort diminished by excision arthroplasty of the acromioclavicular joint at the time of operation. This has not been my experience. I have encountered the reverse; an ugly recession of skin over the site of excision arthroplasty has been troublesome in patients who have undergone this technique. I do not routinely resect the acromioclavicular joint and have had no cause to regret it.

Alternative Techniques

If the bone stock is particularly good, screws alone may be used, but plaster spica protection should be continued for approximately 4 months postoperatively. Very thin patients may not be considered good candidates for plate and screw fixation because of the possibility of erosion of metal through the thin tissues. To avoid the use of a shoulder spica, a Hoffman external fixator may be used, combined with internal fixation with two 6.5-mm cancellous screws.6 External fixation alone has been used; this has the advantage of the possibihty of altering the position of the arthrodesis after surgery. Therefore, in the early postoperative period, if the patient finds that he just cannot manage with the position selected, this can be repositioned by loosening the external fixator and retightening.

References

- McDonald W, Thrum CB, Hamilton SGL: Designing an implant by CT scanning and solid modeling: arthrodesis of the shoulder after excision of the upper humerus. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 68: 208-12, 1986

- Copeland SA, Lettin AW, Scales JT: The Stanmore total shoulder replacement. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 64:47-51, 1982

- Rowe CR, Zarins B: Improvements in arthrodesis of the shoulder. In Post M, Morrey B, Hawkins R (eds): Surgery of the Shoulder, p. 353. CVMosby, St. Louis, 1989

- Richards RR, Kostuik JP: Shoulder arthrodesis, p. 453. In Watson M (ed): Indications and Techniques in Surgical Disorders of the Shoulder. Churchill Livingstone, New York, 1991

- Cofield RH, Briggs BT: Gleno-humeral arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 61:668-77, 1979

- Kocialkowski A, Wallace WA: Shoulder arthrodesis using external fixator. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 73:180, 1991

Suggested Readings

Copeland SA, Howard RC: Thoraco-scapular fusion for facioscapulo-humeral dystrophy. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 60:547-51, 1978

Dewar FP, Harris RI: Restoration of function of the shoulder following paralysis of the trapezius by facial sling fixation and transplantation of the levator scapulae. Ann Surg 132:1111—15, 1950

Rinaldi F: Terapia chirugica nella forma "facio-scapulo-omerale" della distrofia muscolare primitiva. Clin Ortope 16:233-43, 1964